Set in the 1950’s with capable acting, The Gathering is a nostalgic, heart-warming Christmas movie. Unexpectedly, the opening scene introduces DEATH as a life-changing force in the form of a terminal diagnosis. The recipient, Adam Thornton (Ed Asner), is a powerful, proud businessman with a strong personality and a back trail of broken relationships. His response? “I need time. Certain aspects of my life are not in order.” Thornton decides to humble himself and make amends with his adult children. When his doctor forbids the travel needed to do so, his estranged wife (Maureen Stapleton) offers to host a Thornton family reunion for Christmas. This film beautifully illustrates the motivational aspects of our mortality and the need for forgiveness among us.

Set in the 1950’s with capable acting, The Gathering is a nostalgic, heart-warming Christmas movie. Unexpectedly, the opening scene introduces DEATH as a life-changing force in the form of a terminal diagnosis. The recipient, Adam Thornton (Ed Asner), is a powerful, proud businessman with a strong personality and a back trail of broken relationships. His response? “I need time. Certain aspects of my life are not in order.” Thornton decides to humble himself and make amends with his adult children. When his doctor forbids the travel needed to do so, his estranged wife (Maureen Stapleton) offers to host a Thornton family reunion for Christmas. This film beautifully illustrates the motivational aspects of our mortality and the need for forgiveness among us.

Dickens’ classic Christmas Carol is also a film about making amends with those we have ignored or wronged. Like Thornton, Ebenezer  Scrooge (George C. Scott) is a forceful “man of business” but the setting is England during the 1800’s. Rejected as a child by his own father, Scrooge has spent his adult life building wealth. He is a classic illustration of the rejected becoming the rejecting. Consequently, Scrooge has no friends, no fond associates, and no family except for one nephew to whom he is persistently rude. In this film, DEATH comes visiting in the form of apparitions. The first visitor, his former partner Marley, dramatically and regrettably explains that how we live this life greatly impacts the next. Scrooge attempts to comfort him and dismiss him as indigestion. However, Scrooge’s Christmas Eve includes visits from three more spirits—Christmas Past, Christmas Present, and Christmas Future. These spirits cleverly use Scrooge’s own words to convict him when he is faced with the suffering of others. When he views his own solitary death and grave, courtesy of Christmas future, Scrooge is impacted much like Adam Thornton receiving his terminal diagnosis. Ebenezer Scrooge awakens on Christmas morning a changed man, a compassionate man determined to do what he can to alleviate the suffering of others. While the theology is not biblical, the change of heart enacted by George C. Scott is delightful and motivating.

Scrooge (George C. Scott) is a forceful “man of business” but the setting is England during the 1800’s. Rejected as a child by his own father, Scrooge has spent his adult life building wealth. He is a classic illustration of the rejected becoming the rejecting. Consequently, Scrooge has no friends, no fond associates, and no family except for one nephew to whom he is persistently rude. In this film, DEATH comes visiting in the form of apparitions. The first visitor, his former partner Marley, dramatically and regrettably explains that how we live this life greatly impacts the next. Scrooge attempts to comfort him and dismiss him as indigestion. However, Scrooge’s Christmas Eve includes visits from three more spirits—Christmas Past, Christmas Present, and Christmas Future. These spirits cleverly use Scrooge’s own words to convict him when he is faced with the suffering of others. When he views his own solitary death and grave, courtesy of Christmas future, Scrooge is impacted much like Adam Thornton receiving his terminal diagnosis. Ebenezer Scrooge awakens on Christmas morning a changed man, a compassionate man determined to do what he can to alleviate the suffering of others. While the theology is not biblical, the change of heart enacted by George C. Scott is delightful and motivating.

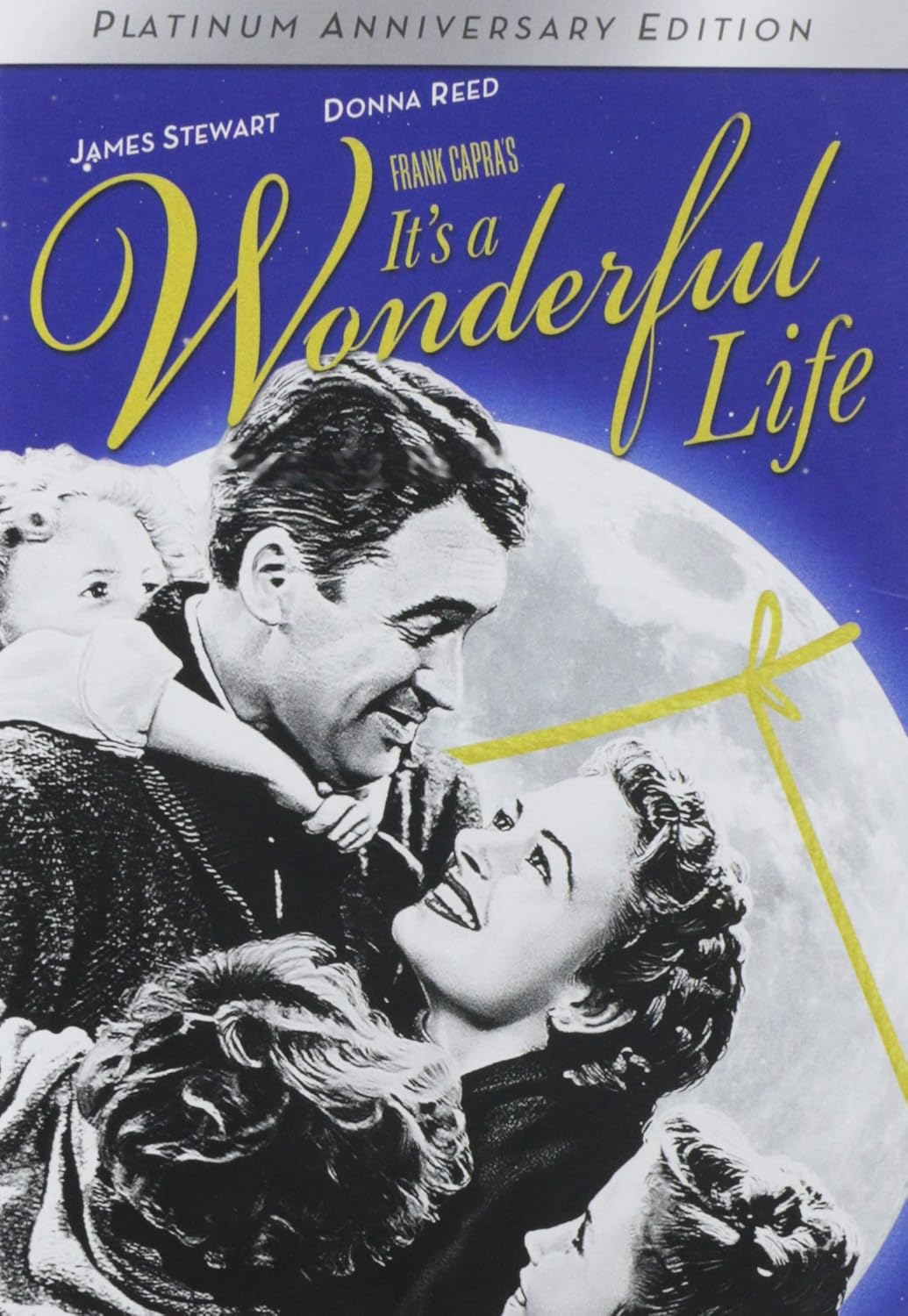

It’s A Wonderful Life is a bit different in focusing on a compassionate man, George Bailey, who runs a local savings and loan for the  benefit of the townspeople. Although travel, adventure, education, and a career in architecture are his desires, George Bailey keeps postponing such endeavors for altruistic reasons. His father’s death caused Bailey to stay in town the 1st time. His brother’s marriage and career choice after college prompted his 2nd decision to stay in town. A run on the bank during the depression terminated his 3rd attempt to leave town. Like many folks, George Bailey continues to do the right things, but self-pity, resentment, and anger grow within. When the 4th crisis comes, Bailey explodes in unreasonableness frightening his family and alarming heaven itself. A guardian angel is dispatched, Clarence, who prevents George’s suicide. George’s rage continues, so Clarence reveals the impact of Bailey’s good works and kind heart in this life—by removing them. DEATH as the change agent in this Christmas movie might be better described as the ABSENCE OF LIFE. Bailey observes what his town would be like if he had never been born, and he is quite changed. George Bailey stops pouting about missed opportunities and becomes truly thankful for what he has—family, many friends, and the satisfaction of having contributed to their well-being. Per Clarence, No man is a failure who has friends.

benefit of the townspeople. Although travel, adventure, education, and a career in architecture are his desires, George Bailey keeps postponing such endeavors for altruistic reasons. His father’s death caused Bailey to stay in town the 1st time. His brother’s marriage and career choice after college prompted his 2nd decision to stay in town. A run on the bank during the depression terminated his 3rd attempt to leave town. Like many folks, George Bailey continues to do the right things, but self-pity, resentment, and anger grow within. When the 4th crisis comes, Bailey explodes in unreasonableness frightening his family and alarming heaven itself. A guardian angel is dispatched, Clarence, who prevents George’s suicide. George’s rage continues, so Clarence reveals the impact of Bailey’s good works and kind heart in this life—by removing them. DEATH as the change agent in this Christmas movie might be better described as the ABSENCE OF LIFE. Bailey observes what his town would be like if he had never been born, and he is quite changed. George Bailey stops pouting about missed opportunities and becomes truly thankful for what he has—family, many friends, and the satisfaction of having contributed to their well-being. Per Clarence, No man is a failure who has friends.

In the recently released Mr. Rogers, a main character, Lloyd Vogel, also harbors deep resentments. In fact, he is so good at tearing people apart with his investigative journalism, no one wishes to be interviewed by him—except Mr. Rogers. Tom Hanks plays the purposeful, slow-paced, and endearing Mr. Rogers. Vogel is continually amazed at Mr. Rogers’ compassion for strangers and sees it as a terrible burden. When asked how he carries such a burden, Rogers explains his daily disciplines: praying, swimming laps, and playing the piano with his wife. The film gives brief glimpses of all three. To Lloyd Vogel’s annoyance, Mr. Rogers asks as many questions as he does. We learn that Lloyd’s alcoholic father deserted him and his sister when their mother was dying. Lloyd himself has been married eight years to a caring woman and has an infant son, but he does not smile, laugh, or seem tender. Like Scrooge or Thornton, Lloyd is perpetually a “man of business.” His father is now dying, yet Vogel finds no reason to listen, care, or interact. Vogel senior, however, is trying to make amends as he faces DEATH. Ultimately, death plays its role and reconciliation is achieved.

In the recently released Mr. Rogers, a main character, Lloyd Vogel, also harbors deep resentments. In fact, he is so good at tearing people apart with his investigative journalism, no one wishes to be interviewed by him—except Mr. Rogers. Tom Hanks plays the purposeful, slow-paced, and endearing Mr. Rogers. Vogel is continually amazed at Mr. Rogers’ compassion for strangers and sees it as a terrible burden. When asked how he carries such a burden, Rogers explains his daily disciplines: praying, swimming laps, and playing the piano with his wife. The film gives brief glimpses of all three. To Lloyd Vogel’s annoyance, Mr. Rogers asks as many questions as he does. We learn that Lloyd’s alcoholic father deserted him and his sister when their mother was dying. Lloyd himself has been married eight years to a caring woman and has an infant son, but he does not smile, laugh, or seem tender. Like Scrooge or Thornton, Lloyd is perpetually a “man of business.” His father is now dying, yet Vogel finds no reason to listen, care, or interact. Vogel senior, however, is trying to make amends as he faces DEATH. Ultimately, death plays its role and reconciliation is achieved.

In these four Christmas movies, characters responded to the change agent of DEATH in a variety of ways. Adam Thornton humbled himself and achieved reconciliation. Scrooge developed new compassion and generosity. George Bailey gave up his bucket list, recognized what is truly important, and found peace. Lloyd Vogel forgave the one who had deeply wronged him and let himself out of the prison of bitterness. How might you and I need to respond to DEATH as a change agent?

Why must our death or that of someone we love be the change agent? This season we are celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ, but his birth is only part of the story. Jesus came as the Lamb of God, to die for our sins, that we may live under grace—unafraid of our own deaths. The death of Jesus Christ was a change agent like none other because He rose again. Jesus conquered death, and opened Heaven’s gates to all of us who confess our sins and receive his forgiveness. We are Heaven bound because Jesus humbled himself and became a baby for us, and Jesus humbled himself yet again on the cross for us. Thank you, Jesus. We celebrate you. Amen.